1. Introducing FSI

FSI Worldwide is an ethical recruitment company which promotes clean supply chains across sectors and jurisdictions at high risk of human trafficking and debt bondage. FSI provides manpower and security solutions, together with specialist consulting services on labour supply chains and security.

FSI has three broad sets of ultimate clients: (i) Western Government clients (predominantly the US Government); (ii) Middle East private sector clients; and (iii) private sector clients elsewhere, primarily in Jordan. FSI supports its clients in ensuring ethical supply chain management and in complying with relevant legal obligations.

The Dhaka Principles for Migration with Dignity, ten human rights based principles developed to enhance migrant workers’ human rights across recruitment and overseas employment, lie at the core of FSI’s approach to recruitment and labour supply chain management. FSI will only operate where the employee contracts abide by the regulations of both origin and destination countries, and where no fees are charged to employees at any point in the recruitment process.

2. The Role of Government in effecting private sector change: US Government Focus

The 2015 amendments to the US Federal Acquisition Regulations require US Government contracts to prohibit Contractors, Subcontractors, and their employees from engaging in severe forms of trafficking in persons, procuring commercial sex acts, and using forced labour during the period of performance of the contract. The Regulations have driven significant change and provided a framework for US Government to procure goods and service in a way that mitigates against the risk of human trafficking.

Businesses seeking to win US Government contracts must evidence steps taken to mitigate the risk of human trafficking in supply chains, in line with the US Government procurement policy. This has become an increasingly important consideration in the procurement process and started to drive change.

The Regulations empower the Government to terminate a contract, and recoup consideration paid for services under it, in the case of breach of human trafficking procedures or codes of conduct. To date, enforcement in cases of breach has been low – human trafficking procedures may be a key element of procurement, however action is rarely taken against noncompliance and policing of implementation is light touch.

This may be changing: it appears that Government is starting to exert significant pressure on contractors to clean up their supply chains. In some cases where debt bondage or other human rights violations have been found in the supply chains of contractors, the contract has been put at risk, with the contractor given deadlines by which they must be able to evidence steps taken to counter the violations discovered or face termination.

The impact of the Regulations should inspire governments internationally to implement similar procurement policies. In most countries the Government wields substantial purchasing power – in the UK it is estimated to be circa GBP 45million annually. This gives governments substantial influence in driving compliance and emphasising ethical recruitment policies.

3. Private Sector Engagement: Middle East

Across swathes of the private sector in the Middle East there is little interest in stopping human trafficking in supply chains. Two large Middle Eastern clients contracted FSI after significant negotiations and external pressure, however quickly stopped recruiting employees through FSI. Many HR departments benefit directly from the majority of recruiters operating in these jurisdictions, where recruitment charges are levied on candidates. Once HR departments realised there were no monetary benefits from FSI as the recruiter, the contracts dried up. This illustrates a common trend across Middle Eastern companies – interest at board room level to effect ethical compliance does not reach HR departments, who see their personal interests flouted.

4. Compliance Drivers: Redress or Reputation

Although few cases have come to court, fear of redress is substantial and growing. In the US there has been some action taken against companies in this sphere, however most settle prior to court and consequently the information does not go public. The key driver for companies, both in the US or in the Middle East, to drive ethical supply chains is redress. Although reputational risk is widely cited as a key motivation in research undertaken regarding compliance with supply chains regulations, in FSI’s experience reputational concerns are secondary to fear of redress and are not driving decision making.

5. The myth of visibility: Challenges of sub-contracting

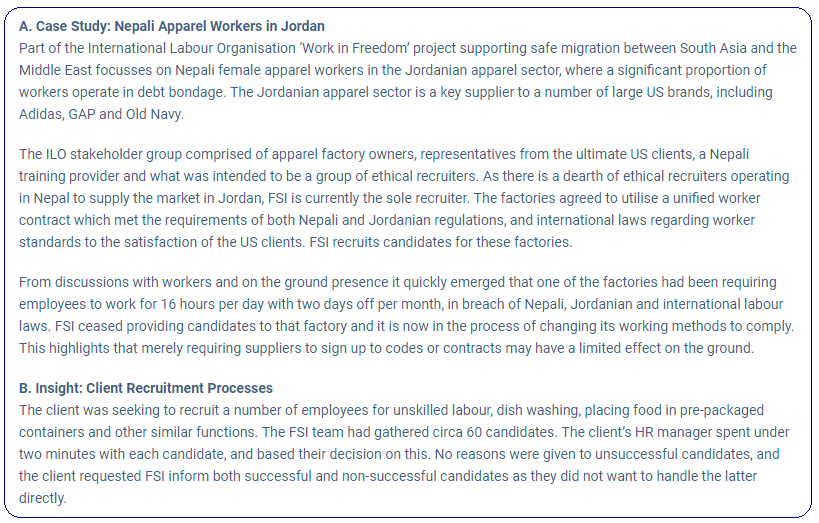

Many companies, including many large construction companies across the Middle East, claim to have full visibility and control of their supply chains. This is largely inaccurate. For example, most Qatari construction companies recruit through Qatari manpower suppliers, and have no visibility over which recruitment agency that supplier uses. Further, as the supplier has no presence in the origin countries, the recruitment chain is extremely opaque. The vast majority of recruitment agencies in the Middle East do not adhere to the Dhaka principles, or even to the minimum requirements regarding recruitment fees and legal compliance enforced by FSI. Consequently, the likelihood employees recruited are operating under forms of debt bondage or other labour abuse is high.

Ensuring the visibility of any supply chain is challenging. FSI’s own supply chain is tiny, largely comprised of agents providing travel, medical and accommodation services. Sub-contractors are bound through their service agreements to abide by the FSI code of conduct, however FSI does not have the capacity to audit how staff are recruited or do broader due diligence on adherence to the code. However, companies can take key steps to enhance visibility, in part by through ensuring the ethical credentials of contracted external recruitment companies.

6. Are attitudes changing?

Within the blue collar recruitment sector there is little evidence of change. International recruitment companies rarely work on blue collar recruitment in high risk jurisdictions, perhaps because the reputational risk of contaminating their brands is too high.

More broadly, there is a stark contrast between attitudes in the US and across a number of Western countries, and those in the Middle East.

There has been a tangible shift in the mind-set of Western Companies, driven in part by rising concern regarding redress, in particular class actions in the US, and the impact of legislation, from the Regulations governing US Government contracting, to companies seeking to comply with the California Human Trafficking in Supply Chains Act or the UK Modern Slavery Act 2015. Many companies which used to be unconcerned about unethical recruitment practices are now significantly more risk aware, however in many cases this merely means they are more covert in their behaviour.

Industry initiatives, such as ‘Building Responsibly’, a coalition of key players in the engineering and construction sector which seek to promote workers’ rights, are evidence of change. By working together they seek to improve standards across the industry, and not merely to use human rights as a competitive differentiator. Industry movements are likely to drive more in depth change than top-down regulation, although the latter is also key.

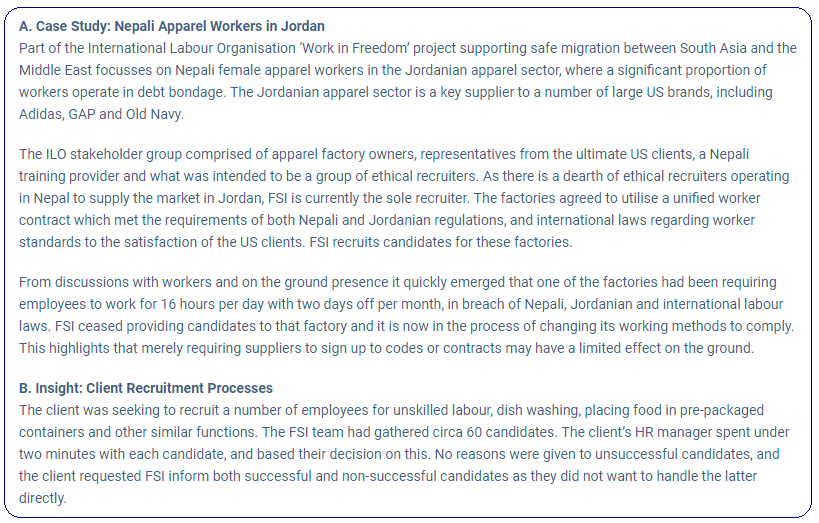

Across the majority of the Middle Eastern private sector unethical recruitment practices are just part of business. Although awareness may be increasing among Governments, particularly driven by international symposia or events such as Expo 2020 and World Cup 2022, little change is trickling down to the private sector. Even where high ranking management or company founders wish to drive change, they typically have little control over the HR departments which profit personally from unethical recruitment practices.