Corporate Human Rights Benchmark: Pilot Methodology 2016

The CHRB pilot methodology assessed the top 100 companies across the agricultural products, apparel and extractives industries on their human rights policies, processes and performance.

The 2018 Corporate Human Rights Benchmark assesses 101 of the largest publicly traded companies in the world on a set of human rights indicators. The companies from 3 industries – Agricultural Products, Apparel, and Extractives – were chosen for the first Benchmark on the basis of their size (market capitalisation) and revenues and assessed across 6 Measurement Themes which have different weightings. Even though average scores are low across the board, overall companies tend to perform more strongly on policy commitments and management systems than on remedy or dealing with key risks in practice.

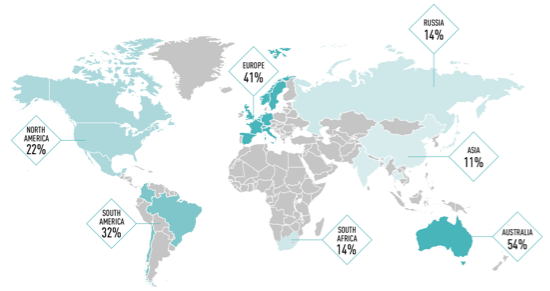

Average scores per region (source: CHRB 2018)

Some key takeaways from the results

The CHRB pilot methodology assessed the top 100 companies across the agricultural products, apparel and extractives industries on their human rights policies, processes and performance.

This Benchmark focuses on 98 companies of the three industries: Agricultural Products, Apparel, and Extractive. It is grounded in the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, as well as additional standards and guidance focused on specific industries and...

For several years now, international media has shone a spotlight on the inhumane working conditions of migrant fishers from Southeast Asia. The vessels they work on reportedly use destructive, illegal, and unreported methods, which take a heavy toll...Read More

However, business leaders need to collaborate in order to do this. My recommendations focus on the need to develop relevant risk management processes and the need to create better systems to share intelligence. I also strongly encourage growing coll...Read More

This regional, comparative study aims to summarize the situation in the Americas, by identifying regional and national policies and legislation on defining recruitment fees and related costs and regulation of Public Employment Services (PES) and Pri...Read More

Modern slavery is the very antithesis of social justice and sustainable development. The 2021 Global Estimates indicate there are 50 million people in situations of modern slavery on any given day, either forced to work against their will or in a ma...Read More